From Company to Colony: the 1890s in Kenya

When it became clear that a commercial company could no longer control Kenya and Uganda (called British East Africa before 1920), the British government took over the administration of the area. In the mid 1890s they adopted the officials of the Imperial British East Africa Company, who were already in situ, and they were a motley lot. One was an illiterate Maltese sailor called James Martin, who managed to get by when a kindly Goan clerk taught him to sign his name; he became a rich merchant in Uganda. There was the one-armed Eric Smith and his assistant W P Purkiss, who loved his pet parrot; both of them laboured to build Fort Smith a few miles from where Nairobi now stands. Purkiss made the bricks from local baked earth. The mad Francis Dugmore was a thorn in their sides – once he sent James Martin’s wife an elephant foot as a delicacy for her table.

Then there was Frank Hall, for whom Fort Hall was named, an active man who got on quite well with local Africans and liked to be out in the field. In contrast was penpusher and meticulous organizer John Ainsworth who tried to set up proper systems of government and was resented by his colleagues as a ‘counter-jumper’ (that is, not a gentleman, but of a commercial background). These people had to persuade the local Africans to honour the British Queen Victoria, about whom they knew nothing.

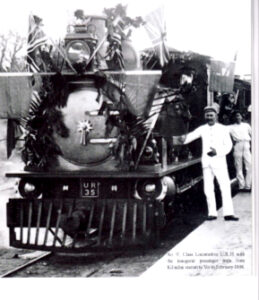

An ‘F’ Class Locomotive UR 35 with the inaugural passenger train from Kilindini Station to Voi in February 1898.

They organized an extraordinary affair to celebrate Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897. “There were two or three thousand natives on the sportsground in Nairobi, entries were very numerous and competition keen. The Masai won the long distance races easily; the sack and obstacle races created immense amusement. The tug of war was splendid, teams of Kikuyu and Masai pulling for nearly 5 minutes before the Masai won. They then pulled against the troops and after three pulls the troops won amidst intense excitement it. There was a grand parade, a general salute, three cheers for the queen and a march past followed by the distribution of the meat of twelve fat oxen.”

When the railway arrived at Nairobi in 1899 there was a champagne lunch with salmon, lobster, beef, beefsteak, pie, partridges, hams, tongues, fowls, blancmanges and all sorts of other sweet dishes. Where the ingredients came from in 1900 is anyone’s guess. The officials, now designated as District Officers, District Commissioners and Provincial Commissioners, were allowed three months’ leave after 18 months, and free return passage to the UK for themselves, but not for their wives and children. In fact marriage was discouraged, and officials often took African concubines. But those days were coming to an end. The railway brought big game hunters, chancers, European settlers and many more missionaries. The stage was set for a very different way of life.

Recent Comments