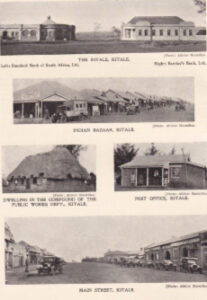

Kitale in 1930

I am grateful to Nick Symes for showing me this letter a farming friend in Kitale wrote to his father: It paints a good picture of Kitale in 1930, the year in which the photographs below were taken.

“Kitale was as far inland and as near the borders of Uganda as any settlers had then penetrated as permanent farmers. The “town” consisted chiefly of the District Commissioner’s house and offices, a little wooden post office and a general store. The nearest railway station was at a place called Eldoret some sixty miles distant over roads in which heavily laden ox waggons generally got stuck in the rainy season. It was not a very attractive place. In 1924, there had been a great Empire Exhibition at Wembley at which Kenya had been well represented. Government officials were stationed in the pavilion to give information and encouragement to prospective settlers. A special and rather extensive pamphlet was issued, giving details of the various industries which were to be developed and painting the future prospects of the Colony in very glowing colours. The Government, in fact, were doing their best to induce people to settle in Kenya. But in this year, and in consequence largely of the publicity obtained at the Wembley Exhibition, many people came out to Kenya and, with purchasers in the market, the price of land increased, and in the more desirable positions as much as from £3. to £5. an acre was being asked and paid, while for proven coffee land anywhere near Nairobi £25 to £35 an acre was asked.

About 1928 that railway from Eldoret to Kitale was finished and passenger trains ran about three times a week. This made a good deal of difference to some of us who had formerly to ship our produce by waggon or lorry from Kitale to Eldoret (where our branch line joined on to the main line between Kisumu, Nairobi and Mombasa). But the people who made occasional trips to Nairobi for business or pleasure mostly preferred to do the 260 miles by car, rather than spend two nights in the very slow train. The roads, however, were really very bad and one started out on a long journey in the rainy season with much more of a hope than a certainty that one would ever arrive. People who have never seen such apologies for roads as then existed could scarcely believe that any car could possibly negotiate such country. The roads have since been greatly improved, much to the annoyance of the railway.

But with the railway the little town of Kitale quickly increased in size. The farming machinery firms opened up warehouses, the oil companies started storage depots, the banks built offices and a general grocery shop opened as well as a chemist and the main street ended up in a line of Indian dukas that sold cheap and gaudy materials, all of Japanese manufacture, to the eager Africans. Fridays seemed to be the favourite day for the outlying farmers to come in to Kitale to do their purchases and to draw their pay rolls from the bank, and at about noon the lounge of the hotel was fairly crowded with ladies taking tea, while the bar was selling drinks. Most of the people used to stop in for lunch and it was the chief occasion for meeting one’s friends and swopping experiences. But I think there was not very much intimate friendship and people did not really blend very well.”

The correspondent mentions the Kitale Hotel, which had recently been built. It consisted of a main building with a spacious lounge featuring a large fireplace with blazing logs in the evenings. There were attractive brick bungalows with up to date bathrooms with hot and cold running water. Guests could sit down to a dinner of high quality cuisine in the handsome dining room with waiters attired in picturesque livery. Electricity was generated by its own plant and in 1930 there were plans to include 20 new bedrooms, a garage, cinema, ice plant and cold storage.

In the early 1950s there was an old man living near Kitale who remembered the place in the latter years of the nineteenth century. Andrew Smallwood writes:

“In 1954 I was taken, by my father, to meet a Mr. Walsh on his farm near Kitale. Mr. Walsh was about 90 at the time. He had been a cabin boy and had jumped ship in Mombasa at age 14 around 1878, 1880. He made his way into the interior and became an ivory hunter in the area north and west of Mount Elgon and on into the Sudan. There were still Arab slavers in this area and from one of these he acquired an enormous flintlock musket which he still had and which he allowed me to handle. Elephant hunting with a flintlock is an uncertain business and Mr. Walsh was much crippled by a lifetime of physical misadventures but still mobile and entirely compos mentis. He was very charming and quite modest about his astonishing life. My father thought that he was, after Burton, Speke and Baker, the first white man in what is now Uasin Gishu, Trans Nzoia and the Karamajong country. He was a boy, alone, while they were well supported aristocratic expeditionaries. Mr. Walsh said that Kitale was in reality Quitale, an Arab name, and when he first arrived, on the site of the present town were still the remains of an enormous thorn bush boma in which the slavers had staged their captives before taking them to the coast. When my father first arrived he said large areas of what is now Trans Nzoia were entirely depopulated, probably by slaving and the ensuing disease and tribal unrest.”

Recent Comments