Interestingly, I had an email about the subject of last month’s blog, about Captain Dugmore, which reads: ‘I have Captain Dugmore’s home service helmet to the 64th Foot, which can be dated to 1878-1881. It has his name and regiment written in the interior and came with a named carrying tin.’

This month we turn from an eccentric administrator to a strange missionary.

What Happened to the Family of Stuart Watt, Eccentric Missionary at Machakos

In 1893 a strange procession arrived at Fort Smith, the Imperial British East Africa Company’s outpost eight miles from present-day Nairobi. Accompanied by African porters, there appeared a white man, his wife, and four children ranging from six months to six years in age. They had marched from Mombasa. Who was this intrepid interloper and what brought him to such a wild place? He was Stuart Watt, an Irishman, a former Church Missionary Society missionary who had decided to travel inland to establish his own independent mission. The CMS denied any responsibility for Watt. ‘You know my opinion of the venture you are making,’ wrote its Secretary to Watt, ‘so I will not write more than to say I pray God to avert you from the catastrophe which your scheme appears to court. I am sure of your zeal. I feel equally sure that it is “not according to knowledge”.’ (J.A. Stuart-Watt’s Recollections, Rhodes House). Watt’s plan was foolhardy in the extreme and John Ainsworth at Machakos fort, where the travellers stopped on the way, had tried to dissuade him from proceeding. Frank Hall, in charge at Fort Smith, also told Watt that his plan was foolish and dangerous. ‘I … decline to be in any way responsible for the safety of the lives and property of your party once out of rifle range of this fort,’ wrote Hall to Watt on 13 December 1893 (Hall’s Diary, Rhodes House).

Watt had already been to Africa as a CMS missionary at Mamboia in Tanganyika, in 1885, but his infant son died there in January 1886 and he and his wife became ill with fever, probably malaria. They had had a daughter, Martha, in East Africa, and she lived. In May 1888 they had abandoned the CMS and Africa and went to Australia, where Watt’s wife, Rachel, thrived and had two more children, Stuart B. in 1889 and (Rachel) Eva in 1891. They bought a suburban residence in New South Wales, with a garden of fruit trees. But, said Rachel, ‘We determined that … we would return to East Equatorial Africa, unconnected with any Society, and open up missionary work in some of those great tracts of country along the Equator.’ (In the Heart of Savagedom). She was doubtful about the plan and ‘the thought of our young children dying of fever or dysentery.’ Yet they sold their house and ‘several properties’ (it seems that Stuart Watt was a bit of a speculator) and decided to finance the mission with the proceeds. They returned to England and Ireland to make plans and settled in Rostrevor, where Rachel had another son, George, in 1893.

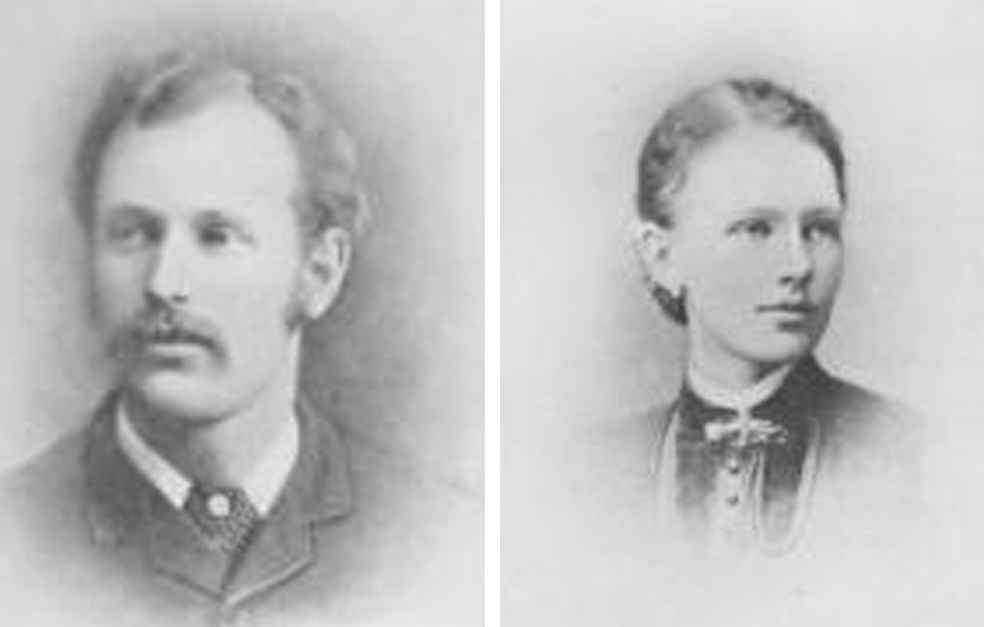

Quite why Watt fell out with the CMS is unclear, but he was to fall out with a great many people in his life. He was not partial to authority. He had been born in the village of Gilford, County Down, Ireland, in 1855/6 but we know nothing about his parentage because the Irish records were burnt in the Civil War in 1922. After school he had been a commercial traveller in the tea trade until he felt the pull of missionary work and applied to the CMS. He also became a captain in the Salvation Army, or so he told Ainsworth. He had met Rachel Harris in Dublin (her ancestry is also unknown, but she was born in Newry, Co. Down, in c.1862) and they married in Carlisle Memorial church, Belfast, a Methodist church, in the July/Aug/Sept quarter of 1884.

Hall described Watt as ‘a raving lunatic’ and what Eric Smith (after whom the fort was named) thought about him was ‘anything but scripturally expressed’ (Hall’s Diary, 14 January 1994, Rhodes House). The family spent Christmas 1893 with Hall at Fort Smith. Watt abandoned his plan of proselytising in Kikuyuland and retreated to Machakos. Ainsworth did not know quite what to do with the band, but allowed them to go eight miles north into Wakamba country to establish a mission at Ngelani. Needless to say, three more children arrived swiftly – Frederick in 1894, James Alfred on 23 August 1895 and Clara in 1898. Watt had no means of financial support, so was obliged to establish a farm. In fact, farming seems to have predominated – Ainsworth reported that there was little sign of missionary activity.

Watt sent to Australia for wattle, previously unknown in East Africa, and to him must go the credit for its proliferation in Kenya. He also sent to Shepherds, a seed merchant in Pitt St., Sydney, for seeds, and ordered from Australia, Tasmania and Japan different kinds of fruit trees. He introduced maize from Virginia. He grew potatoes, passion fruit, tomatoes, and Cape gooseberries. Rachel made boots for the children from wildebeeste hide. ‘Sometimes a feeling of great insecurity would come over me,’ she admitted (p.284). In fact, Watt’s farming was so successful that he swept the board for prizes in Nairobi’s second Agricultural Show in 1902, gaining firsts for apples, apricots, grapes and mangoes, and second for a native bull. (Kenya Gazette, 1 January 1903).

The children were growing up and the eldest needed schooling. Watt was fortunate that a benefactor in the CMS offered to pay their school fees, so Watt set out with the oldest four (Martha, Stuart, Eva, and Frederick) in 1901. The girls were put into a school for the daughters of missionaries at Walthamstow Hall, Sevenoaks, and the two boys were placed in the Methodist College, Belfast. Stuart Watt returned to Ngelani and his wife and other two children. Locusts, jiggers, famine and fires did not deter him from his labours. We don’t know where the children went in the school holidays, but they must have felt a wrench after their free African childhood.

In March 1903 the family decided to visit their children in England and Ireland. In Rochdale Watt attempted to sell his Ngelani farm to the United Methodist Free Church (20 October 1903), but failed. While they were in Dover, another son, Stanley, was born to Rachel, but his birth appears not to have been registered. Soon they were off to Africa again, in November 1904. Martha, the eldest child, returned to Ngelani to help out in 1906, when she had completed her schooling. What happened later to this intrepid family must wait for next month’s blog. Their charmed life was soon to come to an end. To be continued next month.

Recent Comments