A very interesting book has just been published, telling the story of the coming of Goans to East Africa. Many of you will remember Goan clerks, but how did the group obtain a monopoly of such positions, and what else did they do? The answers lie in A Railway Runs Through: Goans of British East Africa, 1865-1980, by Selma Carvalho. Matador, 2014, £10. Available from:

email: books@troubador.co.uk

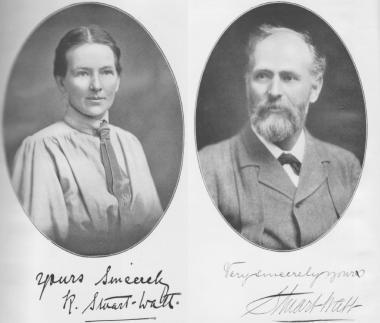

This month we discover the fate of the missionary Stuart Watt, whom I discussed last month.

The Fate of Missionary Watt and his Children

In April I described the life of the missionary Stuart Watt in Kenya, wondering how he could put his family into such danger in the 1890s. Watt attempted to sell his Ngelani farm in 1903 in Rochdale, but seems to have failed because the family returned to Kenya in November 1904. By now he seems to have been more of a land speculator than a missionary, for he also took up 1,000 acres on the Lukenya side of the Mua hills. He had been granted a certificate of occupation by John Ainsworth in 1898 and he managed to convert this into a freehold title in 1905 (Kenya Land Commission evidence).

In 1908 ‘owing to failing health and the necessity of providing a home for their family, most of whom are at school, Mr and Mrs Watt have been obliged to give up their work in Africa,’ reported the Advertiser of East Africa on 24 April. Watt sold 1,000 acres to Northrup McMillan for £1,300, even though no improvements had been made to the land, and Lord Delamere bought the fruit farm, which was now very successful. The Ngelani mission was sold to the American Africa Inland Mission at the same time. Not long after McMillan had

finalised the purchase he was visited by a representative of the Church Missionary Society who had come out from England to take possession of Watt’s land but it was discovered that Watt had put the title in his own name rather than the mission’s, so nothing could be done. Might this indicate that the CMS provided some initial capital for the land? It has been alleged that, after the sale, Watt returned to England, joined another mission, and acquired other land by this means. In any case, and however nefarious his dealings, Watt’s activities prompted the opening up of the Mua hills district to white farming.

The Watts set up home in Branksome Park, Bournemouth. They were there during the 1911 census, when their household consisted of Stuart, Rachel, George (now 17 and a bank clerk), James Alfred (15), Clara (13) and Stanley (6). Their daughters Martha and Eva worked as a domestic nurse and nursery governess at The Vicarage, Cullompton, Devon, in the family of Mary Harris and her children. Could Mary Harris have been a relative of their mother, whose maiden name was Harris? Martha and Eva also appear as evangelical Christians encouraging the Republican Hunger Strike in Ireland. Eva became a missionary, mainly in West Africa, and wrote several books about her missionary endeavours. But where was Frederick, who has disappeared from the record. Does anyone know what happened to him? Perhaps he died, because in July 1899 Watt had described the child as weak and unable to withstand fever (Watt to his wife, c. July 1899, in J.A.S. Watt’s Recollections, Rhodes House).

The wanderlust again visited Stuart Watt in 1913 and he returned to the Mua hills to visit the mission. The family bought land and settled down at Donyo Sabuk, but a fire in February 1914 burnt their house and property. With them were sons Stuart B. (known as Tooty), now 25, and daughter Eva, now 23. On 20 July Stuart senior and junior went riding twenty-five miles away, but the young man developed fever, and died. He was buried nearby. Stuart also developed fever and died on 25 April 2014. He was buried under some forest trees. On hearing of his father’s death, James Alfred left Europe for Kenya in June, to find his mother living in a grass hut. He settled into a tent with his brother George, described by McMillan as ‘as conscienceless as his father’, for eight months while a stone house was built.

George and James Alfred are in the first voting list for the district of Ukamba, in 1919. They lived at Kyatta estate, Chania Bridge (the early name for Thika). By now George had married – Edna Crystelle. Their farm was hit by rinderpest in 1923-4 (Kenya Gazette, 24 October 1923). By 1927 George is in trouble as a debtor (KG, 2 March 1927). Edna Crystelle emigrated to Australia, where she married again – to Hamilton McMaster Allison, probably in 1956. She died aged 67 on 5 March 1964 and is buried at Oakey Creek cemetery, Coolah, NSW. As for James Alfred, he became a clerk on the Kenya Uganda Railway (KG, 10 January 1920). By 1935 he had been promoted to Stock Verifier and by 1938 Accounting Inspector. On 5 September 1922 he married, in Dublin, Amy Feodora Trench (born in Dublin 1896), and they had three sons, two of whom died young. He left Kenya in 1945 and returned to Ireland, where he died in Dublin in 1975.

At some stage Stuart Watt’s wife Rachel also returned to Ireland. She died on 25 June 1932 in Rathdrum and was buried at Greystones, County Wicklow. Her life had been hard, but she must have concurred with her husband’s wild plans to have suffered, as she did, the loss of some of her children and finally her husband.

Recent Comments