Nairobi in the 1920s

After the end of World War I Nairobi started to develop as a town. It had a population of 8,000 Europeans, 8,000 Asians and an indeterminate number of Africans. Lying at mile 327 of the Uganda Railway, it was at an altitude of 5,575 feet, standing at the front of the Highlands and on the edge of the great plains country that led down to the sea over 300 miles away.

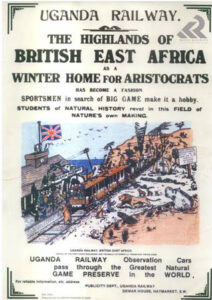

A Uganda Railways poster to popularize British East Africa

Formerly only the headquarters of the Uganda Railway, it had become the seat of the Governor and government offices. It had developed quickly from a mere collection of wood and iron buildings to a town of considerable dimensions. The water supply came from a reservoir 13 miles northwest, and the electric power from a plant 12 miles northeast. There were three banks, two English daily newspapers, a theatre and several churches, these being Anglican, Presbyterian and Roman Catholic. There was also a synagogue.

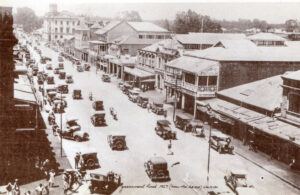

Government Road in 1927

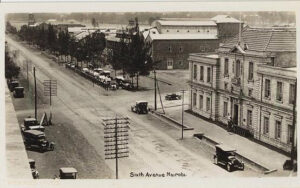

The main thoroughfare was Government Road leading from the station to one of the chief suburbs, Parklands. A less fully developed through road ran at right angles – Sixth Avenue leading to Government House, the hospital, the school, and the chief official residences. Along Sixth Avenue were the Anglican church, the post office and the treasury, all stone buildings. The main suburbs were the Hill, where senior officials resided; Parklands, especially occupied by business residents and with a small English church, St Mark’s; Riverdale separating the Hill from Parklands; Kilimani behind the Hill where there was the headquarters of the KAR; Groganville behind Riverdale which was sparsely occupied. Asians and Africans lived in Eastleigh township, on the east. There was a pretty suburb four miles from Nairobi called Muthaiga between the Kiambu and Nakuru roads. Some bungalows and Muthaiga Country Club, a prominent feature of social life, had been built there.

Sixth Avenue, Nairobi, later called Delamere Avenue and now known as Kenyatta Avenue

It is interesting to hear what outsiders thought of 1920s Nairobi. Margery Perham visited in 1929 and said: ‘Nairobi itself is a disappointing town. I had expected something rather smart and well built. It is one of the shabbiest and shoddiest towns I have seen in my travels, which is saying a great deal. There are hardly any pavements and the roadway itself is most primitive. You either stumble through mud or are blinded by gritty dust. The only decent public building is the railway office. Government House is outside the town. Most government offices are tumbledown tin shacks: the Supreme Court is like an abandoned warehouse…As far as I could see Nairobi was largely peopled with young men wearing corduroy plus fours or shorts, lurid green, orange, blue and purple shirts, and Stetson hats. Some had revolvers in their belts. They imparted a certain reckless Wild West atmosphere to the town but some of them, to judge by their looks, would have to be very careful if they were not to become ‘poor whites’ in the South African sense…Certainly, on the surface, life is very charming in Nairobi, and very sociable, with unlimited entertaining. And in many houses a table loaded with drinks, upon which you can begin at any hour from 10.00 a.m. onwards, and with real concentration from 6.00 p.m.’

This was a period when Kenya was beginning to gain a reputation for outrageous behaviour. When the Prince of Wales visited in 1928 Karen Blixen attended a dinner for him at the Muthaiga Club. She was not complimentary about the dinner guests’ behaviour: ‘Lady Delamere behaved scandalously at supper, I thought; she bombarded the Prince of Wales with big pieces of bread, and one of them hit me, sitting beside him, in the eye, so I have a black eye today, and finished up by rushing at him, overturning his chair and rolling him around on the floor. I do not find that kind of thing in the least amusing, and stupid to do at a club; as a whole I do not find her particularly likeable, and she looks so odd, exactly like a painted wooden doll.’ Things were soon to change for Nairobi and its occupants, with the swarms of locusts and scores of bankruptcies in the 1930s slump.

www.csnicholls.co.uk

Recent Comments