Billiard Balls, Pianos and Elephants

Before the invention of plastics, billiard balls, piano keys, combs and scores of other items were made of ivory. Playing the piano was called ‘tickling the ivories.’ More ivory was used for piano keys than for all other purposes combined. “Ivory, not alone because of the exquisiteness of its contact to the human hand, is the ideal material for the piano keyboard. It is yielding to the touch, yet firm; cool, yet never cold or warm, whatever the temperature; smooth to the point of slipperiness, so that the fingers may glide from key to key instantly, yet presenting just enough friction for the slightest touch of the finger to catch and depress the key and to keep the hardest blow from sliding and losing its power.”

Much of the ivory was exported from the east coast of Africa. Traders made excellent profits from a steady supply, brought to the coast in the nineteenth century by slaves. After slavery was abolished ivory was still provided, as white hunters exploited elephant habitats such as the Lado Enclave, and Africans continued to sell the tusks of animals they slaughtered. Arab and Asian traders transported the tusks to the coast. Governments tried to put an end to the elephant slaughter, but there was still a legitimate trade in ivory well into the twentieth century. The first decade of that century saw Allidina Visram in Mombasa as a primary seller of tusks. A diary has survived from one of his buyers, the American Ernst Domansky Moore (‘Bwana Pembi’), agent (1907-1911) in Mombasa, Zanzibar and Aden for the American firm of Arnold Cheney & Co. He is credited as the largest purchaser of ivory at that time. Moore estimated that 25,000 elephants were killed every year for their ivory. He quickly learnt the tricks of the trade: sellers inserting lead or soaking in water to make the tusks weigh more; he required that the ivory be locked in his warehouse for a week before he would buy it.

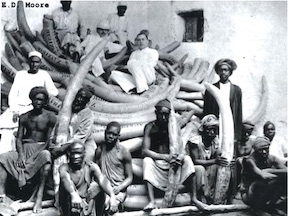

Ernst Domansky Moore, American Ivory Trader

On 6 January 1910 Moore wrote: “Made up our reports and finished accounts today. Altogether I should think it had been a pretty profitable year in New York. We shipped over a thousand tusks from here, and brought in over two thousand bales of cottons. Of course in ivory we beat ’em all hands down, – in cottons we finished just short of Childs, but they bring in unsold goods, and also sell on credit, while we do neither. Altogether I guess we made a few dollars more than they did, in 1909.” On 5 Feb 1910 he summed up his profits: “I have figured up the business we did in the Mombasa Agency last year. At 1/4 and 4.8665, that is, par. the figures stand:

1034 tusks of ivory exported weighing 66054 lbs., worth $187688.76

All exports, worth $ 202830.29

2168 bales & cases cottons imported, worth $ 89094.38

Total exports and imports, $ 291924.67

Average monthly turnover, $ 24327.05”

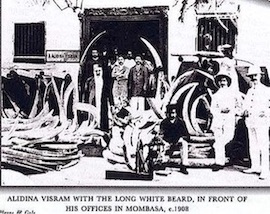

Allidina Visram, one of Mombasa’s ivory merchants.

Moore was always haggling and a merchant named Tejpar seemed to get the worst of it: “Tejpar brought around about fifty tusks today with the best grace he could. After we had weighed and calculated it up, ‘Hakuna nipa one hundred rupees?’ in his English – Swahili. ‘Hapana kabisa, Bwana Teipar. Si kasi yako. Hi kasi Bwana Vining. Wewe sema ‘Siweze tapata, lakini MAPATA, tasamma?’”

E D Moore sitting on a pile of ivory in Mombasa.

Moore returned to the USA and became a critic of the ivory trade. Allidina Visram became very wealthy, having 240 shops in Kenya when he died in 1916. He had taken advantage of the progress of the construction of the railway and opened stores along its length. He was a considerable philanthropist, endowing schools and hospitals in Kenya.

Allidina Visram with tusks in Mombasa in 1908.

www.christinenicholls.co.uk https://www.europeansineastafrica.co.uk

Recent Comments