Egerton: the Lord, the Farm, the College and the University

As a third son, Maurice Egerton never expected to inherit the Barony of Tatton and the Tatton Park estate in Cheshire with its grand residence, Tatton Hall. But his eldest brother William died in infancy and his other sibling Cecil died at school at the age of seventeen. Born on 4 August 1874, Maurice was kept carefully at home by a mother who dreaded losing her third son, and he was educated privately. His lack of social contacts and school friends during his adolescent years made him very shy and uncomfortable in large gatherings; in fact, he had few social skills. Nonetheless he developed an interest in photography, aviation, travelling, collecting and motor sports. In 1910 he had a serious plane crash which left him limping for the rest of his life. Some time was spent accompanying his father on travels around the world.

He joined the forces at the outbreak of World War 1, serving in the Royal Navy. He was then eligible, under the soldier-settler scheme, to apply for land in Kenya, where he settled in 1920, the same year that he inherited the barony. He was granted land at Ngata. Later he bought a 120,000-acre farm at Njoro, where he developed a flock of 25,000 sheep and 2,500 cattle. This farm was managed by Hugh Coltart. Egerton divided his time between his Kenya property and Tatton Park in Cheshire, where he was a generous lord of the manor, particularly to the young, for he had a passion for helping boys. He often invited schoolchildren from the poorer districts of Manchester to Tatton Park for the day. In 1946 he founded Egerton Boys’ Club. The daughter of the Tatton estate blacksmith said, ‘Everyone called him Lordy. He was a warm, lovely man, very kind. During the war he had logs cut from the estate and put at the top of each street in Knutsford for people’s fires. When he came to the farm, he always wore an old greasy mac and flat cap. Nobody would know who he was unless they knew him personally. There was no side to him, no show.’

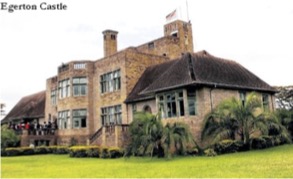

In Kenya, he displayed his special interest in the welfare and training of young men by establishing in 1940 Egerton Agricultural College at Njoro, on 860 acres of his land which he gave to the Kenya government. It provided courses for young men interested in farming. This college became the present-day Egerton University. Meanwhile, in the 1930s he began to construct at Njoro a four-storey 82-roomed building copied from the design of Tatton Hall, which he called Egerton Castle. The design was neo-classical with natural dressed stone walls, slate tiled roof, steel casement windows in recessed carved timber frames and panelled and carved timber doors carried in arched timber frames. Floors were mostly finished in polished parquet, with coloured ceramic tiles for wet areas and smooth cement screed for work areas. The building was not finished until 1954, after which Egerton lived in it. A recent visitor (the house is now a museum open to the public) wrote: “The walk through the 4-storey castle feels like a time travel into chivalry. The man had mastered his delectable traits, I can tell by the large wine cellar situated in the basement. The castle has many bathrooms with defunct electrical machines that would be used to warm towels and dry hair, with at least four to himself. The rest were for male kids, guests and the ladies (despite the irony that no woman took a shower in there during his tenure). There’s a large safe and two food stores: one was for imported foods and the other for local products.”

Egerton Castle is open to the public as a museum.

Egerton Castle is open to the public as a museum.

“The kitchen had a mini slaughter-house. The chef would have to shower and perfume himself before cooking Lord a meal. A doctor would drive from Nakuru twice a day to come inspect his food,” states Robert [the caretaker]. “It also surprises me that all the rooms are numbered. Lord Egerton’s bedroom door number is 20 and locked. It still has some of his personal effects, ” he explains, adding, “all 53 rooms were numbered because we had a lot of businesses running around here, it was easier that way to avoid getting lost.”’

Lord Egerton died in his Kenya castle on 30 January 1958. Unmarried, he left no heirs and the barony became extinct. There is a possible apocryphal story about a fiancée who jilted him, but he could have been unattractive to women, being only 4 feet 6 inches tall. He left his farm to its manager, Hugh Coltart. The enormous death duties on his English properties were assuaged by his donation of Tatton Park and Hall in Cheshire to the National Trust. Egerton University flourishes in Kenya – a fitting tribute to this most philanthropic of men.

Recent Comments