Here’s a note on Olive Grey who I wrote about in my November blog. A relative in Australia has kindly given me the place and date of Olive’s death. She died in Poona, India, on 20 October 1920 and was buried there on the following day.

Purkiss’ Parrot

William J Purkiss, a former merchant marine officer, originally arrived in east Africa as an employee of the Imperial British East Africa Company in about March 1891 and was employed on building the narrow-gauge railway to Mazeras—the grandly named Central African Railway. The railway was soon abandoned and some time the following year Purkiss was sent to Fort Smith in Kikuyu as Assistant Superintendent. Following the death of the Superintendent, Robert Nelson, in December 1892, Purkiss became Acting Superintendent.

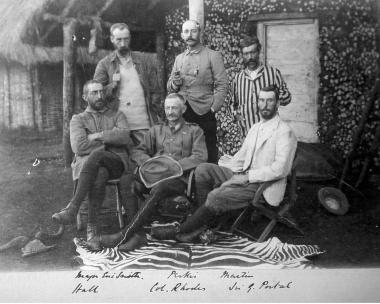

(The photo that opens this blog is probably taken at Fort Smith. Purkiss in in the middle of the second row.)

Before he died Nelson, who had been with the H.M. Stanley expedition to ‘rescue’ Emin Pasha, had managed to infuriate the neighbouring Kikuyu with his aggressive attitude and indiscriminate raiding of their villages for food and cattle. When Sir Gerald Portal passed through the area on his way to Uganda in February 1893 on his Special Mission, he found the residents of the fort living in a virtual state of siege. Anyone venturing more than fifty yards from the perimeter without an armed escort was very likely to be attacked and killed. Purkiss managed to wound and capture an assailant, the Kikuyu leader Waiyaki, who died on his way to exile at the coast and was buried at Kibwezi.

As there was no food available locally Portal was delayed at Kikuyu while sufficient provisions were collected at Machakos for the next part of his journey. By the time Portal reached Kikuyu he was already firmly convinced that the Company was moribund. But he did have good things to say about Purkiss who was trying to reduce the tension and bring about a return to peaceful trading. During his enforced stay at Kikuyu, Portal was much taken by a grey parrot which, as he mentioned in a letter to his wife, kept him company as he wrote. The parrot belonged to Purkiss.

Portal probably passed on his views about the imminent demise of IBEAC, and Purkiss, already deeply disillusioned, is listed as resigning from the Company in April 1893. However, he was still at Kikuyu when Portal passed through on his return journey from Uganda to the coast in August 1893 and when offered a temporary position with the new administration in Uganda he accepted. He arrived at Mumia’s on his way to Kampala in late September 1893. In February 1894 he was given a permanent appointment as a 2nd Class Assistant to the Uganda Protectorate and was part of an expedition up the Nile to Wadelai. He apparently became ill during the expedition and was eventually moved to Eldama Ravine where he failed to improve. In July 1894 it was decided to take him to the coast. He died at Kibwezi, about 190 miles from Mombasa, on 15 August 1894, and, ironically, was buried in the mission cemetery close to his former attacker Waiyaki.

The usual procedure at the time was to sell locally the deceased’s effects, except personal items such as rings and watches, and the proceeds were then used to pay off their bills (in most cases it seems these were for accounts with local traders for alcohol) with any residue being sent home to their next of kin. In this case, however, the Foreign Office appears to have required all the deceased’s effects to be sent to England. Soon the Consul-General at Zanzibar, Sir Arthur Hardinge, was being asked why the effects had not been sent. Purkiss’ father was in frequent communication with the FO and the FO with Zanzibar. This appears to have had little effect on speeding up the authorities at Mombasa as it was almost six months after Purkiss’ death that the effects were eventually dispatched. They included a live parrot.

Why the parrot was sent is unclear, but maybe the months of nagging by the FO may have had had an effect. However, it was later noted by Charles Hobley, another Company man, that Consul Hardinge ‘probably never took his duties seriously’ so it looks as if sending the parrot could well have been Hardinge’s idea. The eight boxes of clothes and curios, and the live parrot, eventually arrived at the FO. The presence of the parrot was quickly noted and an urgent request sent to the next of kin for it to be collected without delay.

There is a rather sad postscript to the story. Keys for two of the boxes were sent, with a request that they be passed on to the family. For some reason these were never given to the family but ended up in the FO files—probably filed away before the boxes arrived. The keys were attached to a sheet of paper and bound into what became FO 107 at the National Archives, Kew, where they still are. Presumably Purkiss’ father had to break open the boxes.

Christine Nicholls and Stephen North

Recent Comments