The Kakamega Goldfields

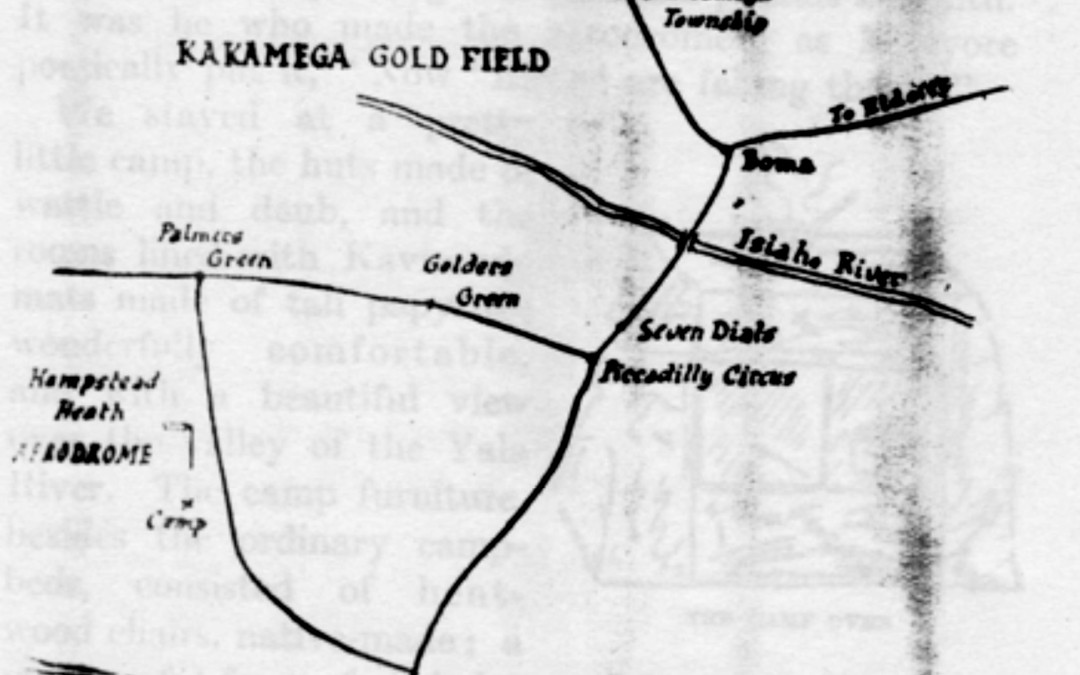

The recent interest in gold in the Kakamega district reminds us of the first gold rush in the region – in the early 1930s. In 1930 Kakamega township was an open space with a few Indian dukas, but in the middle of the decade it became a prosperous and crowded township. What had caused this transformation? The worldwide slump had occasioned the bankruptcy of many settler farmers and when in October 1931 an American, Louis A. Johnson, a farmer at Turbo and formerly a storekeeper in the Klondyke, turned up in Eldoret with gold he had found at Kakamega, impoverished settlers flocked there to earn a living. Johnson had been alerted to the possibility of gold being in the area by A. D. Combe, of the Uganda Geological Survey, who wrote a report in 1930 on a geological reconnaissance of parts of North Nyanza Province and recommended that prospecting be carried out there. The new arrivals panned for gold on the Yala and other nearby rivers and sank shafts at Kimingini reef. By 1932 there were 200 of them and they had established a settlement. After passing the government boma (the District Commissioner’s office) you crossed a river, and went past ‘Seven Dials’ on a good road up to ‘Piccadilly Circus’ where there were many camps formed of reed matting. The huts were thatched and surrounded by little gardens. From ‘Piccadilly Circus’ you continued to Golders Green, with its lovely view, then to ‘Palmer’s Green’ and finally ‘Hampstead Heath’, where there was an aerodrome, built by an American speculator, de Ganahl. The first miners who found gold at Kakamega put it in Eno’s Fruit Salt bottles to take to the bank in Kakamega. The town boasted three hotels, a Corkscrew Bar and several European shops.

The government stepped in to regulate matters and one-year (renewable) mining licences had to be purchased for twenty shillings in Kisumu. The maximum size of a claim was 300 feet by 100 feet. About eighty percent of the miners panned solely for gold in streams, while the rest searched for reef gold. By February 1932 1,700 claims were registered. ‘Lorries are arriving laden with household goods as evidence of an intention to take up more permanent residence. Three types of prospectors have arrived. The first is the man who is willing to work hard with his hands in the hope of making a reasonable living; the second is the business man anxious to acquire plots in the township for the purpose of trading; and the third is the type anxious to obtain options on properties.’ (Spectator, 12 December 1932) ‘Men and women are seeking feverishly for fortunes…Into this veritable Garden of Eden the vultures are fast descending from all parts of the world…people in all walks of life are giving up practical things for golden dreams. Millionaires are seeking further riches, and clerks have forsaken their office stools, hoping to become millionaires. There are company promoters galore hoping for the gold feast, hard bitten prospectors who have trekked from farflung goldfields; an American clergyman, full of faith; former schoolmasters; and all manners and kinds of men, and even women…There are gold camps-de-luxe. I saw the camp of an American dollar millionaire…He is mining in grand style, with full equipment. His camp is electrically lighted. Tinned caviare and champagne are brought to him from the base. He even has an ice-making plant. In the same neighbourhood are to be found two young clerks from Johannesburg who left their jobs in search of a fortune…I came across a tough old prospector from Abyssinia [Ethiopia]. His sight had almost gone looking for gold in the gold rushes of the past fifty years…He was examining the dirt through a large magnifying glass. He implored me not to tell his native boys of his infirmity, otherwise they would not work for him…A former schoolmaster was about to give up in despair. Then his eyes lighted up as he got sight of a golden glitter. It was one of the biggest gold nuggets found in the field – worth over £400.’ (Daily Express, 23 February 1933)

From 1934 alluvial mining declined, becoming secondary to reef mining. Word spread and foreign mining consortia built mines and operated on a large scale, but after three years most of them left. The two biggest mines that remained were Rosterman’s and Risk’s, and they engaged in deep-level mining (as deep as 600 feet by 1937, and 1,940 in 1946). Mining by individuals began to level off. From 439 in January 1934 numbers fell to 384 in February that year. One of the problems was the high incidence of malaria in the region. In 1938 there was a further diminution in mining because the proximity of the Italian-Abyssinian war prevented investment and capital dried up. That was the year gold had its highest proportion in Kenya’s export commodities, being the second largest export earner. Then World War 2 intervened and by 1952 the gold boom was over.

Recent Comments