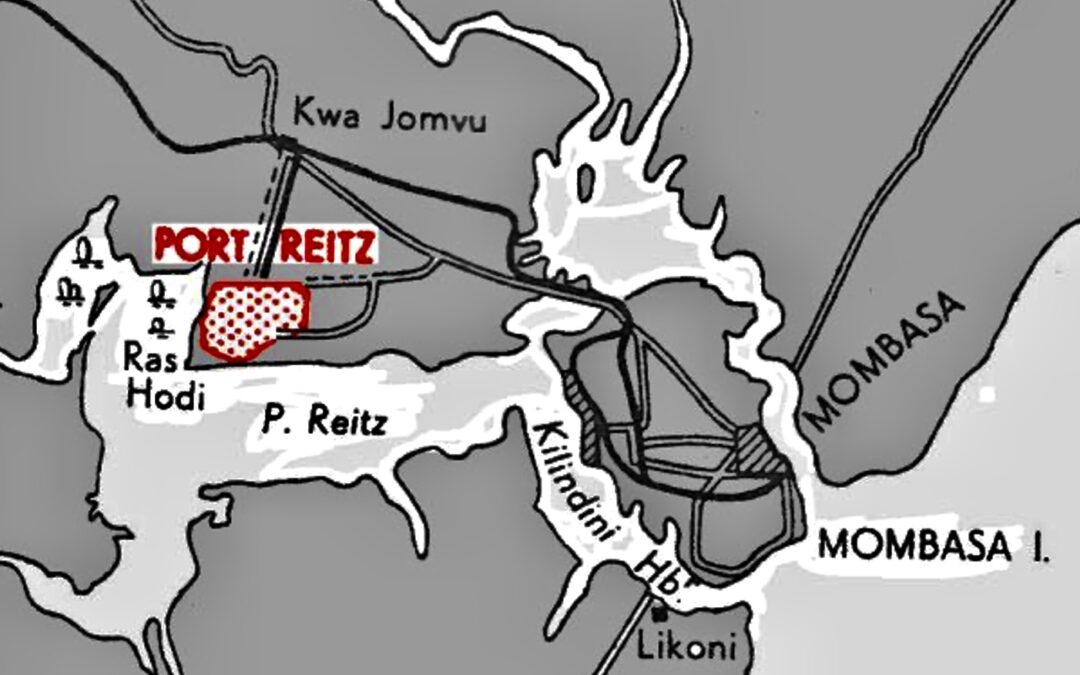

To the north-west of Mombasa island is an inlet and on its mainland side is a flat piece of land later named Port Reitz. It is now the site of Mombasa’s Moi International Airport.

Why was this area called Port Reitz? In 1824 a young lieutenant in the Royal Navy set off from Mombasa on a donkey with 70 others, some on donkeys, some on foot, to explore the coast south of Mombasa. He had been left in Mombasa with midshipman George Phillips and three other seamen to keep the peace after Captain Owen had declared that Mombasa was British. The man on the donkey was John James Reitz, the son of Jan Frederik Reitz, a captain in the Dutch Navy who had settled in South Africa at the time of William of Orange, the Dutch monarch with hegemony over the region. In 1814 Cape Colony was ceded to Britain. Johannes Jacobus, who became John James, was born in Cape Town on 3 May 1801 and he joined the Royal Navy on 29 April 1814, serving in HMS Stag. For the following few years Reitz served on the Spartan in the Mediterranean, the Cherokee at Leith, and the Salisbury in the West Indies.

Promoted to lieutenant in 1921, he was sent to Woolwich to join the Barracouta. This was a new ten-ton brig under the captaincy of A. J. Vidal and its orders were to sail with the Leven captained by W. F. Owen to Cape Town, to survey the east coast of Africa from the Cape to the shores of Arabia. On the way to the Cape the Barracouta anchored at one of the Cape Verde Islands where Reitz wanted to climb Bird Rock. The rock broke from under him and he was cast into the sea, fracturing his thigh and ankle. He was rescued and left at home in Cape Town while his bones healed. From then on he walked with a limp. He rejoined the expedition which reached Mombasa on 11 February 1824.

Captain Owen had ambitions that Mombasa would be ruled by the British; while he waited for approval from the British Government he left in Fort Jesus, with a union flag flying above the fort, John James Reitz, George Phillips and four others. Phillips was an excellent linguist, fluent in French, Portuguese and Spanish; he also picked up Arabic, making him invaluable as an interpreter at Mombasa. Reitz was provided with 12 freed slaves to act as his guard, but they frequently deserted or were absent without leave. The British seamen in the garrison were also badly behaved and had to be flogged. Reitz was given a plot of land by a local woman at Kisauni on the mainland, on which he could settle the slaves he was determined to free. He did indeed settle a few ex-slaves there, at a place later to be called Freretown. In his free time he played his flute. His shipmates described him as “a good musician, and in possession of an uncommon share of wit and good humour, together with a pleasing frankness of manner that made him respected and beloved by his companions.”

Captain Owen had encouraged Reitz to explore the coast north and south of Mombasa Island. He decided to go southwards to Pangani. With 70 men, a few riding donkeys and the others on foot, he set out from Mombasa when it was already raining. On 6 May he sheltered in a cave near Shimoni and the following day passed Wasin Island and carried on to Mkumbani where the party was due to meet boats that had sailed from Mombasa to take them back to Fort Jesus. However, he discovered the boats had gone on to Tanga. Because the donkeys were exhausted Reitz decided to go to Tanga by canoe but he was battered by a storm and washed out to sea before finally making Tanga. Though the rainy season was now in full swing, Reitz carried on travelling by canoe to Mbweni, which he reached on 13 May. On the following day he went down with fever, which grew progressively worse. The rest of his party decided to return him by boat to Mombasa, reaching their destination on 29 May 1824. Reitz died in malarial delirium as his boat was approaching Mombasa harbour.

George Phillips planned the funeral: “For the internment of the remains of this much lamented officer the interior of the ancient Portuguese cathedral was chosen. A grave seven feet in depth was dug near a ruinous piece of masonry, that alone indicated where once the altar had stood. The corpse, decently erased in fine cambric, was conveyed to the cathedral, followed by a procession of the first people of the town. The funeral service was read, and the body consigned to the earth with military honours. A humble specimen of Arab masonry, plastered over and whitewashed, marks the spot.” Although attempts have been made to find the grave, it has not been discovered. George Phillips and one of the other men also died in Mombasa, but we do not know where they were buried.

www.christinenicholls.co.uk https://www.europeansineastafrica.co.uk

Recent Comments