Thomson in Maasailand

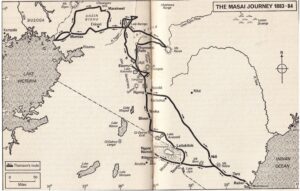

Recently there have been articles in Old Africa about the Maasai, so it would be interesting to look at early European contacts with those peoples. In 1877 Maasai warriors had prevented Johann Maria Hildebrandt, a German botanist, from travelling beyond Ukamba on his way to Lake Victoria. Henry Morton Stanley described the Maasai as particularly warlike and for several years the area in which they lived remained unexplored by Europeans. But there was increasing interest in the early 1880s from botanists and geographers and the Royal Geographical Society decided to sponsor an expedition to penetrate Maasailand. Joseph Thomson, already in Zanzibar, was asked by the Society to design a scheme and create a budget .

Screenshot

John Thomas Last, a missionary stationed out in Mamboia, advised that anyone wanting to march into Maasai country should have some amount of force, but much more important was the traveller’s manner towards, and treatment of, the Africans. Thomson was an ideal person to lead the expedition as he was particularly good in his dealings with Africans, being not a bully and sympathetic their point to view. What Thomson and the Royal Geographical Society did not know was that a German expedition under Gustav A. Fischer was also attempting to cross Maasai territory. That expedition was forced to return at Lake Naivasha when confronted by belligerent Maasai warriors who branded some of its porters on the forehead.

Thomson reached Siha, on the lower slopes of Mt Kilimanjaro. There he learned that Fischer had quarrelled with the Maasai and blood had been shed. Thomson met his fist Maasai moran (warriors) at Kibongoto, who told him of the blows that had been struck against the Fischer group and the resultant deaths of two women. However, the moran agreed to allow Thomson to enter their land. Thomson paid his hongo, or tribute, suffering manhandling by the Maasai with good grace. It soon became clear, however, that the passage of his expedition was disputed and the Maasai clan under the leader Mbatian wanted to avenge the deaths inflicted by Fischer’s men. Thomson had to march back round Kilimanjaro to Taveta. He returned to Mombasa for supplies of more goods for hongo. He decided to move northwards round Kilimanjaro from Taveta, to the Ngong hills. Entering the grazing lands of the Iloikop branch of the Maasai, he moved warily past Loitokitok towards Lake Amboseli. The expedition was treated with great indignity by local people. Thomson wrote: ‘It is quite impossible to picture the wretched life we were now called upon to lead among the most unscrupulous and arrogant savages to be found in all Africa, who indeed looked down upon all other tribes as inferior beings. Even with our large caravan we had to submit with the meekness and patience of martyrs to every conceivable indignity. Though they had pulled our noses, we should have been compelled to smile sweetly upon them.’ Thomson himself assumed the guise of a laibon and his unfamiliar whiteness caused some locals to treat him with awe. He was assisted by Eno’s Fruit Salt which when mixed with water seemingly magically frothed and bubbled. He was allowed to travel on, skirting the Rift Valley and climbing several thousand feet to the Kaputi escarpment, where the Maasai were even more insolent than previously. Eventually he reached Ngong, where he camped for two weeks.

Thomson now traversed Kikuyu country until he reached the Maasai again on his way to Lake Naivasha. At Naivasha once more he had to submit to daily indignities – to put off and on his boots, to wiggle his white toes, to permit his skin to be stroked and his hair to be pulled. He was, however, somewhat admiring of the Maasai’s arrogance, physical stature and appearance. As they differed radically from the Bantu-speaking Africans he regarded them as higher on the scale of humanity. Interestingly, he contrasted the Maasai with the subgroups of Kwavi and Iloikop whom he regarded as physically more degraded. In particular, the Njemps Iloikop had had to turn to agriculture when they lost their cattle and they had distinctly degenerated, he thought. There had been a long series of wars between the Maasai and their Iloikop cousins; he gave valuable written testimony about the last war and the consequent dispersal of a Iloikop segments in his book Through Maasailand. He obtained his historical information from indigenous and Zanzibari sources, and from questioning the Maasai elders at Naivasha.

Thompson then wanted to go to Mount Kenya and would therefore have to cross Laikipia. This he achieved with the aid of Eno’s Fruit Salts and by removing and replacing his false teeth. He reached the Uasin Nyiro river on 28th October at the base of Mount Kenya. Hearing that he was about to be attacked by warriors he fled in the direction of Lake Baringo, following elephant tracks. From Baringo he went to Mt Elgon and the lake later to be named Lake Victoria. His journey back to Mombasa belongs to another story.

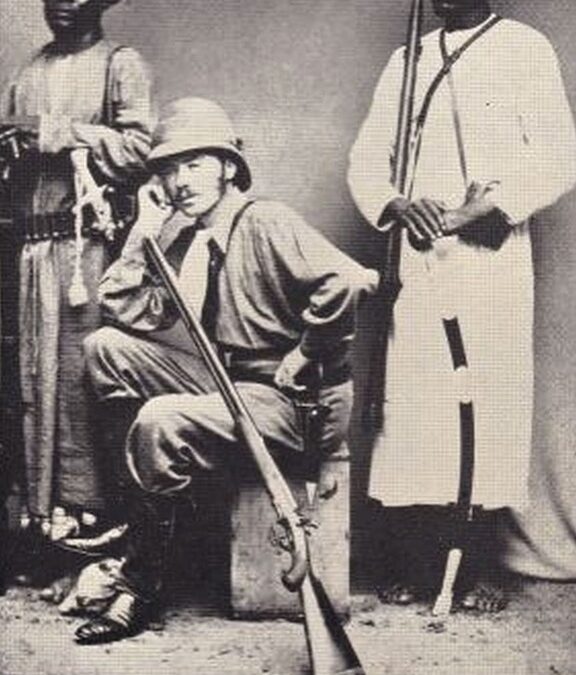

Despite hostility from local groups, Thompson’s exploration of the lands beyond Kilimanjaro was remarkably successful. He had penetrated through the most dangerous tribes in Africa, traversed a region unequalled in that continent for the interest and magnificent variety of its topographical features, and for the unique peculiarities of its inhabitants. He added significantly to Europe’s knowledge of the region and he provided unrivalled ethnographic data and numerous photographs. He made scientific discoveries of plants and animals, including the gazelle which is now named Thomson’s gazelle. His journey did a huge amount for the geography of Africa. His success was partly due to his character and attitude. He had faced difficulties cheerfully and endured insults with patience. He had dealt with aggressive peoples without shedding any blood. He opened up eastern Africa to European scrutiny, which was to have a profound effect on the history of the region.

www.christinenicholls.co.uk https://www.europeansineastafrica.co.uk

Recent Comments