A Most Unusual Missionary

Charles Henry Stokes was far from being your traditional missionary. Irish, excitable, easily swayed, unreliable, passionate, he regarded the making of money as a most important aspect of life. To this end he deviated from his missionary calling and it is alleged he became a gun runner. But he had his virtues. Unlike many of his contemporaries, he respected Africans and never ill-treated them. He was therefore able to become a most successful leader of caravans from the coast to the interior before roads and railways were built. He first appeared in East Africa in 1876 as a lay missionary, under the auspices of the Church Missionary Society. In this role he soon gained expertise as a leader of caravans to Uganda, and in 1885 he left the CMS. He became an independent trader and could be hired in Zanzibar as a caravan leader, sometimes with as many as 2,500 African porters. He always kept his word with the porters.

Stokes’s business ventures prospered and he joined the German service in their territory as an Assistant Commissioner. His trading exploits apparently included the trading of guns and powder for ivory. This was his downfall. The Belgians in the Congo were most unhappy that he was supplying Africans with guns and began to suspect, wrongly, that he was trying to foment rebellion against Belgian rule. One Captain Lothaire, in charge of a disturbed district in the Congo, determined to put a stop to the alleged gun running. He decided that execution was to be an appropriate punishment. He captured Stokes, gave him a summary trial by court martial, and sentenced him to death. ‘He was hoisted on two packing cases; the cord was passed round his neck; the packing cases were removed; the body fell suddenly; it was thus he died.’

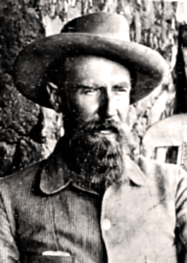

Charles Stokes

A considerable fuss was made about this, even though the British Foreign Office regarded Stokes as anti-British and pro-German. Sir John Gray, the British consul in Zanzibar, said that ‘he was no loss to us, although he was an honest man.’ But the British and Germans could not let the Belgians get away with the atrocity. They forced the Belgians to put Lothaire on trial for murder, but he was whitewashed. Eventually Queen Victoria had to intervene with her cousin King Leopold of Belgium, and the matter was settled when the Belgians paid £8,000 compensation to both the British and German governments.

Stokes left a legacy of a complicated personal life. In fact, he had not left the CMS of his own accord – rather, he had been dismissed because he had married a non-Christian African. Originally, in 1883, he had married an Englishwoman, a member of the Universities’ Mission to Central Africa, but she had died in childbirth in 1884. Her infant daughter Ellen Louisa was sent to England to be cared for by relatives in Shrewsbury and subsequently by Stokes’s sister in Dublin. Then, on 27 July 1886 Stokes had undergone a marriage ceremony at the Consulate General, Zanzibar, with Limi, daughter of the paramount chief of the Wanyaturu from central Tanganyika. The marriage with Limi produced no children. Stokes’s liaison with a concubine Kabula Njiri produced a daughter, Louisa, who died at a mission station in 1895. Kabula herself died in Kampala in 1968. Stokes assumed Muslim clothes and subsequently accepted two concubines from the King of Buganda, Nanjali and Zaria, relatives of the Prince of Koki. Nanjali gave birth to Stokes’s son Charles Kasaja, in 1895, a few months after his father’s death. He was taken to Scotland by Mrs Walker, the widow of a missionary. He trained as a medical orderly and organised the blood transfusion service in Uganda. He married and had eight children, dying in 1994.

Much of this information was derived from Peter Ayre’s database which I am editing. It is hoped to put the database on the web later this year.

Recent Comments